The Declaration of Sentiments was one of the most important documents of the women's movement of the 19th century. Read about the Declaration's author, origins and goals, then test yourself.

Life Now and Then

Take a moment to think about the world you live in today. Who is allowed to vote? Who is allowed to own property? What rights do single women have that married women do not? What about the rights of men vs. women? These all sound like pretty obvious questions. Anyone over the age of 18 legally eligible to vote. Pretty much anyone can own property. Married women and single women have the same rights. Flashback to roughly 170 years ago, and the answers to these same questions were much different.

In most states, only white men who owned property were allowed to vote, not women. Very few women legally owned property. Any property that a single woman owned became her husband's property after she got married. Sounds pretty crazy, huh?

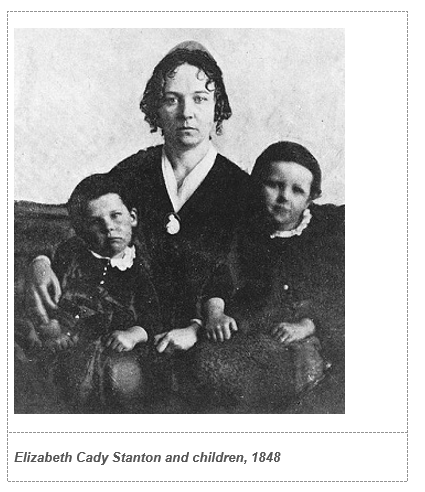

Well, other people thought so to. In 1848, a group of men and women met at the Seneca Falls Convention to discuss such unfair laws and the goals of the women's movement. One of the leaders of that event was Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

Elizabeth Cady

Elizabeth Cady was born in 1815 in a fairly well to do family in New York. Like other women of her social standing, Stanton received an education, but not the kind of education women receive today. She learned how to be a proper lady and was not allowed to attend college. In Her early 20s, Stanton spent a lot of time visiting her cousin, Gerrit Smith, a well-known abolitionist who fought to end slavery. At the age of 25, she met Henry Brewster Stanton, one of Smith's friends. The two of them married quickly, then sailed across the Atlantic Ocean to attend the World's Anti-Slavery Convention in London, England.

Much to Elizabeth Cady Stanton's dismay, she was not allowed to even enter the convention. Can you guess why? Stanton, along with many others, was barred from the event because she was a woman. While in London, Stanton met fellow abolitionist Lucretia Mott, a Quaker. The two of them, upset with this sad state of affairs, discussed having a convention to discuss the rights of women.

However, life intervened; after the convention, Stanton returned to the United States where she and her husband continued to fight against the institution of slavery. Between 1840 and 1847, Stanton and her husband had seven children. Although she loved her family, she was frustrated by the fact that her status as a woman really only allowed her to be a wife and a mother.